For 15 years, Olivier Kruschinski travelled to every match of his team, FC Schalke 04. He cheered in the stands and sympathised when the German championship failed to materialise. He shared his passion for the Royal Blues with his father and passed it on to his son. "The first thing I did after the birth," says the mid-four-year-old with a grin, "was not go to the registry office. No, he went straight to the clubhouse to register". That must be true love. And it is. Anyone who calls Olivier a Schalke fan today, however, "is insulting me. I'm not a fan, I'm a Schalke fan! Being a Schalke fan is part of my identity and therefore also the answer to the question: Who am I actually?" DeinNRW met Olivier Kruschinski in what is perhaps Germany's most famous neighbourhood.

Coal and football are, of course, inextricably linked in the history of Gelsenkirchen. This is because 150 years ago, Essen entrepreneur Friedrich Grillo brought thousands of miners from Poland to the coalfield. The tranquil town of Gelsenkirchen grew into a sizeable city with 400,000 inhabitants. And FC Schalke 04 was something like the first "works team". In the 1930s/40s, 14-year-old boys also travelled to the pits here during the day.

Today, "only" 250,000 people still live in the central Ruhr district city. Mining has disappeared and with it the miners. But the people took "their Schalke" with them, "which is why there are Schalke strongholds all over the country today", as Olivier Kruschinski knows. So when a home match of Bundesliga club FC Schalke 04 kicks off on a Saturday in today's Veltins-Arena, which incidentally is not in Schalke, but in the exact geographical centre of Gelsenkirchen, in the district of Erle, many fans have to travel several hundred kilometres to get there

Meanwhile, the place where the club celebrated its greatest successes, where FC Gelsenkirchen Schalke 04 became German champions seven times, has been crumbling for years. Wild grass is growing over the history of the legendary Glückauf stadium. Nevertheless, Kruschinski and his fellow campaigners from the "Schalke Mile" project have managed to have a sign erected in front of the entrance with the blue lattice gates that reads "Ernst-Kuzorra-Platz". And in the stadium, where youth footballers now play on artificial turf, two large-format photos are now reminiscent of the time when 70,000 people - still dressed in hats, suits and ties after going to church on Sundays - cheered their heroes on the sidelines. If you allow yourself to do so when visiting the already slightly overgrown stands and simply close your eyes for a moment, you may be able to hear them and suddenly find yourself right in the middle of that very special feeling of togetherness from back then. This is the moment when even non-footballers are gripped by the magic of this forgotten place.

"Football was an outlet for them to get out once a week - church - pub - curve - clear their heads and project their own wishes, dreams and hopes onto the pitch."

The visitors accompanying him on his "Mythos Schalke" tour that day nod before taking their seats one by one in Ernst Kuzorra's favourite place in the rustic clubhouse with its 1960s charm and having their photos taken. They breathe history. Club and city history. And when Olivier then talks about how, as a child, he himself was once allowed to serve his idol - the man who, despite a hernia, shot Schalke to the first German championship in 1934 and thus became a living legend - a beer and a shot, a little pride and reverence resonates in him too.

At the same time, the Gelsenkirchen city guide with the unusual tattoo on his leg and the relaxed tone of voice regrets that the potential that lies in this district and its eventful history is only gradually being recognised. The much-praised Schalker Markt, for example, is now a worn-out car park ("I never said that Schalke is only beautiful"). The old railway line of the Consol colliery, which was once the birthplace of the "Polacken- und Proletenclub" S04, so to speak, has been decommissioned. Nature has long since made its way back to the sites of industrial heritage, transforming them into almost mysterious places that invite discovery.

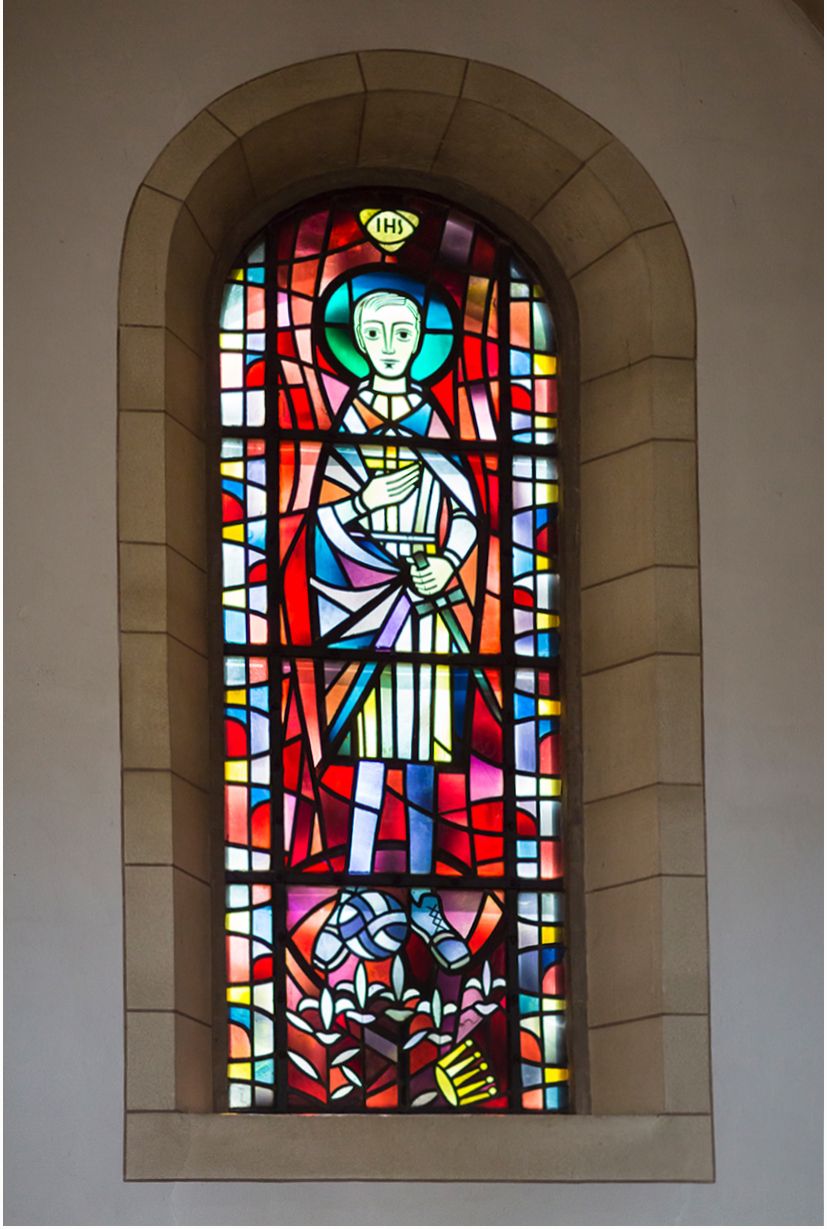

One such place is St Joseph's Church. Hardly anyone outside of Gelsenkirchen knows what unique thing it has to offer. A stained glass window directly opposite St Barbara, the patron saint of miners, shows St Aloisius - with football boots, socks and a football. Olivier Kruschinski knows of no other church in the world that has anything similar. He even had the window tattooed on his left calf.

The busy and self-confessed local patriot, who has also written a football travel guide and founded the label "Echte Legenden" (Real Legends), is all the more pleased that "the grains are slowly taking root". Since the "Schalker Meile" project began in 2006 with its commitment to the neighbourhood, fan initiatives have settled here again. Signs have been renewed, facades painted. Almost the entire street - with the exception of one yellow house - is blue and white. And in the neighbourhood office of the Schalker Meile project, there are scarves and shirts with the winding tower and inscriptions such as "One city, one greeting! Glückauf from Gelsen".

The Schalke fans return to Schalke and gather at St Joseph's Church, where a blue and white wall with fan mail, scarves and jerseys bears witness to the solidarity of the people with their city and the club. And they celebrate peacefully with the fans of the opposing team.

This togetherness, getting into dialogue with people, is also important to Kruschinski when he goes to the stadium himself or taps his own beer at the after-work market in Gelsenkirchen's city centre.

"That was a typical boozy idea",

Fun eventually turned serious. For Olivier, the idea of finally bringing a Gelsenkirchen beer back onto the market is also "a commitment to the regional and local", something that has accompanied him throughout his life. With the two cellar beers, which are of course sold in brown "Plopp" swing-top bottles with the old Glückauf logo, Kruschinski and his colleagues want to continue the tradition of the former "Glückauf beer". This was brewed until the 1980s in the Ückendorf district, where Kruschinski now lives with his family in his grandfather's old colliery house. Since then, there hasn't been a single brewing kettle in Gelsenkirchen, which is why GEbräu and GEsöff are still brewed in Weserbergland. But Olivier already has an idea (again)...

Three questions for Oliver KruschinskiCycling through the Ruhr region

Olivier, you have 48 hours of free time. What would you definitely do with this time in NRW?

Olivier: Right now? A whole weekend? That's quite simple. With the nice weather, I'd spontaneously get on my bike and cycle the Ruhr Valley cycle path. I go on a cycle tour like this once a year with my group. That's great. You can cycle everywhere in NRW, especially on the many disused railway lines.

Which place in NRW did you recently rediscover for yourself?

Olivier: Oh dear ... that's difficult. I haven't done anything other than NRW for 20 years. Yes, I can think of one: I recently went to the Silbersee in Haltern for the first time. A day at the beach in the middle of the Ruhr area, that was really cool. I used to ride past there a lot on my motorbike, but of course you experience the area in a completely different way with children.

Your personal favourite place in NRW.

Olivier Kruschinski: Definitely Schalke. What else? But basically my favourite place is where I live. In Ückendorf, with a view of the Hohewart and Rheinelbe slag heaps and right next to the old railway line. I can walk and cycle here. This is where I feel at home.